[A personal story by Carol M. Hodgson: "When I go home I'm going to talk Indian"]

[September 8, 2000 - Remarks by the Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of Indian Affairs]

[February 6, 2001 - An excerpt from the Winter 2000 Issue of Native Americas Journal]

[December 17, 2001 - An excerpt from the book "Shaping Survival"

Four Native women sharing their educational experiences]

[January 6, 2003 - Hampton Normal & Agricultural Institute: American Indian Students (1878-1923)

Personal Accounts written by students and student lists by name and Tribal affiliation]

[April 9, 2003 - A class action law suit Zephier, et al. v. United States of America filed by former

reservation school students.]

The Reservation Boarding School System

in the United States, 1870 -1928

Justification and Rationalization

Day Schools vs. Boarding Schools

Carlisle Indian School and Richard Henry Pratt

The System Begins to Fail

|

By way of introduction: The Reservation Boarding School System was a war in disguise. It was a war between the United States government and the children of the First People of this land. Its intention was that of any war, elimination of the enemy. The reason this war is difficult to recognize is because it was covered by the attractive patina of a concept called "Manifest Destiny." Manifest Destiny was a philosophy by which the white european invader imagined themselves as having a divine right to take possession of all land and its fruits. The reason that the Concept of Manifest Destiny was so effective was because, as it steam rolled across the land, it dragged the masses with it. The hooks that dragged these masses were many and were forged by Christianity and the Christian imprimatur. Although the fuel that energized Manifest Destiny was economic, the inspiration was in its alignment with divine will. This quote from the essay "God and the Land" illustrates this alignment:

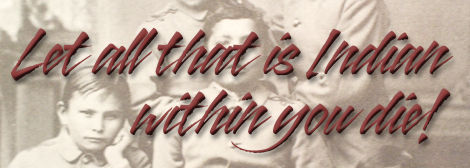

The reservation school movement was "invented" by the descendants of those who rode the Manifest Destiny band wagon. Educating Indians was the refinement of the times, a continuation of the process, its effort was to confine Indians to sedentary life and open more land for use by whites. The "reformers" of the 1890's were just another group of torchbearers...doing their part in this ongoing process of cultural genocide and providing additional strands to strengthen the rope that forms the noose of genocide around the neck of Native people. To the white pioneer and his government, education of Indians was a convenient, and at the time, attractive adjunct to the efforts to "settle" this land. To these white Christian people and the ersatz Indian educators, to "kill the Indian, save the man" was an appealing as well as justified idea. In any encounter with mainstream historical accounts, it is obvious that Native People were very little more than a "problem" to be solved by the colonizers. To white society, they were heathens and behaved like savages. They had no written language, their children were unschooled, and for the most part they didn't know how to stay in one place, many moved their villages according to the seasons. If these people, these Natives, were ever going to amount to anything in this United States of America, they had to be taught the proper and acceptable way to live. All aspects of Native culture or way of life were unacceptable to the white european mind. As this country's use of land increased and as "civilization" moved west, the Indians remained a problem. The developing white society felt that it was obvious, to anyone with eyes to see, that these people with such a primitive lifestyle needed to become civilized in order to survive in American society. Additionally, in order for this American society to have the land to expand, the Indians had to be moved out of the way. The european settlers, mostly Christians, were convinced that "Christian" civilization was for this land and it inhabitants, the ideal, the goal to be achieved. And it was their belief that it was in keeping with Divine intent that society move forward toward ever more desirable stages of cultural development. In comparison to white christian culture, Indians lived a savage, subsistence way of life. The Tribal organization and the adherence to "paganism" were a reflection of a lesser, a lower form of society. Many reformers believed that Indians were in fact not intellectually inferior but lived and organized their lives in an inferior manner. Because of this way of thinking, it was deemed that indeed Indians were worth "saving." Contact between whites and Indians became more prevalent as the century wore on and it became clear to the white settlers that something would have to be done so that Indians might become productive members of this new American society. Government Indian Policy was coming increasingly under fire from Congress as well as many well meaning voices from the Christian pulpits. The "Indian Rights Association" group with its roots in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, sought to reform the government's relationship with the Indian Nations. Philadelphia provided the venue for another group, the "Women's National Indian Association," while in Massachusetts the "Boston Indian Citizenship Association was formed. These so called "reform" or "support" organizations recognized that Indians had been handed only lies, trickery, disappointment, and in some cases, death in exchange for the land that was taken from them. It is obvious, at least to me, that these people thought of themselves as obligated to "do" something to remedy a situation that was going from bad to worse. The organizations vowed to make amends by seeing to it that Indians would receive the education that would ultimately make them productive members of American society. I find it difficult to understand why the concept of respect for Native people never seemed to develop itself in these philanthropic reformers. Absolute assimilation of was the goal of white society and nothing short of the complete elimination of Native culture would satisfy them. So clouded by their sense of their own superiority these "civilized whites" were unable to see the value of another culture.

Many whites saw the "social evolution" of the Indian as a progressive process that could be accelerated by education. Education also promised to relieve the government of the cost of feeding and clothing Native people by encouraging and providing the tools for economic self-sufficiency. Waging war on Indians and protecting frontier communities was also costly and it was thought that in this area too, education could save money. Then again there was the question of land:

The reservation day school was the first part of this venture into Indian education. The children lived in the village with their families and attended school nearby during the day.

Speaking any language other than English was strictly prohibited, as was any attempt to adhere to any Native spiritual practice. The force that lay behind these prohibitions, is readily seen upon reading this statement from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs E.A. Hayt:

In a relatively short time it was decided that as a tool for assimilation these day schools were not and would never be successful. The children were too close to their homes, families and cultures to be fully and successfully indoctrinated with white society's language and values. The next step was to establish reservation boarding schools that were located near the agency headquarters. Children attending these schools were only permitted to go home during the summer months and perhaps for a short period at Christmas time. Even with the children removed from the daily influence of home and family, the assimilation process was not proceeding at an acceptable pace as far as the government was concerned. One of the reasons was, it was found that parents often came to visit their children, thus allowing the children the opportunity to speak their language and stay in contact with their tribal ways. This was distinctly counter-productive in the eyes of the assimilationists The third and final plan to be adopted was the off-reservation boarding school. This was finally to be the way to rid Native children of their language and culture. The children were sent, in many cases, hundreds of miles away from family, language and Native ways. What started as an experiment with Indian prisoners, soon became the model upon which this latest educational effort was patterned. In St. Augustine, Florida, with volunteer teachers, Lt. Richard Henry Pratt, the officer in charge of a group of Indian prisoners at Fort Marion, began to teach the Native prisoners the white man's language. With the teaching of the language came heavy doses of Christianity. Separation of church and state seemingly did not apply when it came to Christianizing Indians. In the 1890's the US government in the name of the Indian Office stipulated that students in government schools were to be encouraged to attend churches and Sunday schools. The reformers, the government and society in general, knew Christianity was essential for the development of the "good" Indian. It mattered little at the time that the governmental mind and the Christian mind were in fact one. Church and state shamelessly walked hand in hand.

Pratt arrived in 1875 in Florida with the prisoners and by the end of 1878 he was told that he was free to continue the education of the Indians being released from prison. After spending one year at the Hampton Normal and Industrial Institute, Pratt was permitted to take his students to an unused military barracks in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Thus was the beginning of one of the most significant of the residential Indian schools. Carlisle and Hampton were the beginning of the system of schooling for Indian children that would prevail into the next century. At one point Pratt was told that an Army officer's place was with his regiment. Pratt answered angrily and with passion with a letter sent to President Hayes:

In the opinion of the government and the white Christian reformers, the reservation schools were not only good for the Indian, but they were good for the surrounding community. The schools provided employment for local residents, and regularly purchased supplies from local merchants. The students themselves were a welcome source of cheap labor for the owners of the surrounding farms. At Carlisle, Pratt required students to live with "good white" families for at least part of every school year in order to see the benefits of having good moral character and living in the nuclear family structure as opposed to the tribal structure. This "outing" program, as Pratt called it, was to give the students "first hand" knowledge of civilization, and the beneficial influence of Christianity. The policy makers proceeded towards their goal of assimilation in an orderly manner. The students, upon their arrival, were required to have their hair cut short, an act that produced much resentment among the new students. Tribal dress or clothing was not permitted as school uniforms were provided and required to be worn. Their children's names were another connection to their home and family and so they too were changed and new "pronounceable" names were assigned to each. No effort was spared when it came to breaking the Native cultural ties. The school, the new physical environment, was also used as a teaching tool. The wild and natural was pushed back and orderly, managed grounds were constructed. The land was tamed, controlled and conquered and mirrored the process outlined and established to deal with the students, all an expression of the power of the white man. The formality and order of the English garden was an elemental expression of civilization, and therefore another useful, illustrative educational tool. Never think for one minute that the Native children attending these schools were not at every turn reminded of their lesser status in comparison with white society. There was great effort put into building character, instilling good morals and responsible citizenship, even though it would not be until 1924 that the Curtis Act declared that all Indian people to be citizens of the United States. As I encounter information about how this period of government schools began and subsequently developed, I find myself wondering how the idea of assimilation never left a sour taste in the reformers collective mouths. The children in these schools were captive in much the same way that a prisoner is captive. Regimentation, structure, discipline and uniform clothing were characteristic of the reservation school system, and all established to produce the glorified end of making one culture disappear into the underbelly of another. The fact that any of these children succeeded in remaining connected to their tribal ways after their experience in the government school system is remarkable. They seemed resilient in the face of oppressive disrespect. On February 1887, the General Allotment Act, or the Dawes Act became law. By way of offering context and some definition, I offer this short excerpt from Ward Churchill:

Two years later, the Indian Office directed that all schools use the anniversary of the passing of the Dawes Act as an opportunity to impress on the students the opportunity given to them by this legislation. A new school "holiday" was therefore created, called "Indian Citizenship Day." The Native students were treated as though they were new immigrants in their ancestral land. I am going to quote some lengthy excerpts from Adams' book "Education for Extinction," because I think one can get a better sense of the pressure of the assimilationist intent from reading the original wording. The excerpts are from a stage production written by Helen Ludlow and performed at Hampton in 1892. The name of the piece is "Columbia's Roll Call." All of the "players" are, of course, Indian students. How much more "instructional" it is to be able to participate in a stage production than to merely view it. I can only imagine how difficult it must have been for some of the students, and how rewarding and edifying for their teachers. It seems to me that it takes a certain kind of twist in a mind to create something such as this, and force Native students to be a part of it. The pageant's structure revolves around the mythic American goddess Columbia, who summons forth, one by one, familiar historical figures upon whom she bestows a badge of citizenship. "The first figure to step forth is none other than Columbus...he describes the moment when land is sighted.

Captain John Smith comes forward then Miles Standish and Pricilla Alden, next is John Eliot the puritan missionary, followed by George Washington. As these historical heroes, all of them white, make an appearance, each is given the badge of citizenship. The next to speak is an "Indian" character who pleads:

Indians were now willing to join the white man's march of progress.

Columbia replies by challenging the Indians to name individuals of their race equal to those white heroes "that have made me great and established my throne in the New World."...One by one they come forth. There is Samoset, whose lines are, "I said to my paleface brother, welcome Englishmen." There is the chieftain who says to Washington, "We welcome you to our country." And an Indian convert recites a Bible verse in Algonquian. In the end Columbia is convinced. She gazes upon a group of Indians dressed a farmers, teachers, and mechanics. Their plea for a place of honor and citizenship seems too reasonable to deny, and she says to her Indian wards: "You have gained your cause. Your past, your present, and your purposes for the future prove your right to share all I have to give. Take my banner, and your place as my citizens." (Adams, pp.196-9) What arrogance and gall it took to write those words and demand that they be spoken by Native tongues. How like salt ground into the wounds already inflicted on the Native people. The idea that children were coerced to speak these words that reversed the truth is hard to imagine. Indian people were being told that they in effect had a right to "share" in what had belonged to their ancestors. The divinely driven concept of Manifest Destiny could be couched in no more descriptive words than those of Helen Ludlow. Many Indian parents resisted sending their children to the reservation schools, and opposition was widespread. Indians agents had strong powers of persuasion in this regard. Sometimes rations were withheld from uncooperative families, and in cases where there was continued resistance, police were sent to take the children by force. The "fanaticism" of the Ghost Dance was blamed for some of the opposition to sending Native children to the boarding schools. Some students, after arriving at the school became so ill that they had to be sent home and some students displayed their resistance by running away. The children who remained frequently practiced their culture and spoke their language in secret and in fear. In any case the schools had difficulty both in gaining the student's cooperation and attracting the support of the parents. For those students who did not resist, it was a matter of practicality; many were convinced that their choice was between assimilation and extinction. Past associations with whites had taught Indians that they were never again to be permitted to live on their own terms. The buffalo were all but gone and the freedom to travel as their ancestors had, was gone. Graduation ceremonies at the schools gave further opportunity to reiterate the white agenda.

The reformers who had so strongly supported the idea of education as a tool for assimilation began to see that the desired end was not forthcoming. Some students returned to their homes and to their tribal ways and others although not returning completely to their old ways, became in a sense "bicultural". Those who so strongly supported Indian education viewed neither of these situations as a success. As support for reservation schools began to wither, voices of opposition began to rise. The schools were criticized as tools for making Indians dependent rather than self-reliant. Schools were criticized as cruel for separating the children from their families. The structure and political support for the philosophies and activities of the reservation boarding schools was fast eroding by the early 20th century. The writings of Zitkala-Sa and others were encouraging the development of new educational theory. One of the voices of the child study movement, G. Stanley Hall..."urged teachers to build on an Indian child's natural capacities and background rather than obliterate them. Hall asked, " Why not make him a good Indian rather than a cheap imitation of the white man?"" Regardless of this seeming reasonable movement away from the overt assimilationists, these new philosophies were not remarkable for their respect for Native culture. Quite the opposite, these new thinkers were never willing to acknowledge the equality of Native Culture. So, even if the rhetoric had changed, the intent remained the same. In 1928, a report entitled "The Problem of the Indian Administration", otherwise known as the Meriam Report, was produced at the direction of the Indian Commission. The Meriam report was highly critical of government Indian policy with regard to education. The poor quality of personnel, inadequate salaries, unqualified teachers and almost non-existent health care were some of the criticisms leveled by the report. The assimilationists had failed, Indian culture had survived. The misguided efforts of the reformers had profound negative effects on the Native children. For a People that had endured almost 400 years of oppression, the reservation school system was just another of the deplorable anti-Indian actions of white America and its government.

Adams is correct; the war at the turn of the last century was waged against the children. But, fortunately for this country, the children had not listened to those who told them to "let the Indian within you die." One would think that would be enough to open the ears and eyes and the mind of white America - that war against children, but sadly it is not. America still has her "Indian problem." Native people are still told to "get over" the past. America remembers what it did to its Black slaves and is sorry. America remembers what happened to the Jews in Europe and says "never again." America refuses to remember what it has done to Native people, it wants to forget the lies and the slaughter. Think, America. Remember what happened. And meanwhile... The war continues; the genocide has not stopped. Shame... Endnotes: David Wallace Adams, Education for Extinction - American Indians and the Boarding School Experience 1875-1928, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, 1995.Ward Churchill, Since Predator Came - Notes from the Struggle for American Indian Liberation,Aigis Publications, Littleton, Colorado,1995. Michael Coleman, American Indian Children at School, 1850-1930, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, Mississippi,1993. M. Annette Jaimes, ed.,The State of Native America - Genocide, Colonization, and Resistance,South End Press, Boston, Massachusetts, 1992. Statement by the Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of Indian Affairs Included in the remarks of Kevin Gover, Assistant Secretary-Indian Affairs Department of the Interior at the ceremony Acknowledging the 175th Anniversary of the Establishment of the Bureau of Indian Affairs September 8, 2000, were the following comments:

The entire text of the remarks made by Gover is available here Links to Related Sites: The Seattle Times, February 3, 2008 - "Tribes confront Indian boarding school's painful legacy."More than 70 years ago, Native American children suffered abuse and loneliness at Indian boarding schools. Now, tribes and others in Washington and nationwide are reaching out to elders, their children and their children's children in hopes of repairing the damage. (text of article can be found here) The New York Times, January 31, 2008 - "Australia to Apologize to Aborigines." The new Australian government of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd will apologize for past mistreatment of the countryıs Aboriginal minority when Parliament convenes next month, addressing an issue that has blighted race relations in Australia for years. (text of article can be found here) Indian Country Today, April 21, 2004 -- Boarding school abuse didn't break Lakota aerospace engineer - The story of Seymour Young Dog (text version of article) Canada - Hidden from History - Voices of the Candian Holocaust

Canada - Native man leads class-action quest for residential school compensation

From the Minnesota Historical Society site - Indian Grammar, Primary and Day Schools: The Purposes of Government Explained.

NAMING THE INDIANS - BY FRANK TERRY, SUPERINTENDENT OF U. S. BOARDING SCHOOL FOR CROW INDIANS, MONTANA.

An excerpt from the Winter 2000 issue - An Article concerning the reservation schools in Canada. Native Americas Journal: EDUCATION-THE NIGHTMARE AND THE DREAM A SHARED NATIONAL TRAGEDY, A SHARED NATIONAL DISGRACE BY BRUCE E. JOHANSEN.

Central Michigan University Site - the Clarke Historical Library This discussion of federal education policy toward Native Americans and the experiences of Indians who attended off-reservation boarding schools includes the following components: Federal Education Policy & Off-Reservation Schools 1870-1933 Assimilation Through Education:Indian Boarding Schools in the Pacific Northwest - University of Washington web site with photographs. Duke University, Native American Education: Documents from the 19th Century. LISTENING TO NATIVE AMERICANS: Making Peace With the Past for the Future The Colonization Process - We Must Do The Necessary Thinking For Them, by Jordan S. Dill. The Only Good Indian is a Dead Indian - The History and Meaning of a Proverbial Stereotype. American Indian Stereotypes: 500 years of Hate Crimes, by Stephen Baggs. Dead Indians, Live Indians and Genocide An article "The Indian Question Past and Present" by Herbert Welsh, secretary of the Indian Rights Association, which was published in the October 1890 issue of The New England Magazinep.257 is available online at Cornell University's Making of America Journals Collection. An Indian Boarding School Photo Gallery This Hampton site: Provides a roster of students (1878-1892), arranged by Tribe. The student rosters presented on these pages were found in the U. S. Senate Executive Document No. 31, 52nd Congress, 1st Session, entitled Letter from the Secretary of the Interior in response to Senate resolution of February 28, 1891, forwarding report made by the Hampton Institute regarding its returned Indian students. This document was ordered printed February 9, 1892. The Sherman Names Project Student Archives: A searchable index of names of the many students attending Sherman Indian Boarding School from 1890 to 1939. Fort Lewis Indian School Carlisle Indian School Sherman Indian School |

Comments on this material by Sonja Keohane are welcome.

Return to Index

Return to Poetry page

Page endnotes and links updated 3 June 2008

All material on this site, except where noted:

Copyright © 1999-2009 Sonja K. Keohane

All Rights Reserved